On June 22, 1855 the editor of The New York Times lamented the fact that "a small party of citizens of New-York have clubbed together and subscribed fifty-thousand dollars for a statue which has been modeled by our countryman, H. K. Browne [sic]." The editorial noted "Our New-York monument will be an equestrian statue of gigantic proportions, and will be placed in Union-square."

The New York Times was clear in its condemnation of any statue. It applauded the fact that during the Revolution the British statues had been destroyed. "New-York, as yet, is free from any monumental pillars or effigies, and the fact is most creditable to the good sense of our practical and busy people." The writer applied the logic that in ancient times monuments were necessary to record history. But the invention of the printing press had done away with that need. "A nation that has books has no need of monuments," insisted the editor.

Saying that "Every child knows Washington," and "his history is on every book-shelf," the article contended there was no need for a monument. The editor called the raising of statues "idolatry, "and said "a monument is something repugnant to the common-sense of a practical and intelligent people."

The "small party of citizens" who had raised the funds for the Washington statue included some of the wealthiest and most powerful men of New York--among them William Astor, August Belmont, Peter Lorillard, James Lenox, Robert B. Minturn, Robert L. Taylor, and W. C. Rhinelander.

Henry Kirke Brown was in the last stages of the two-year project when The New York Times editorial was published. An apprentice sculptor, John Quincy Adams Ward, who would become one of America's great artists, had been highly involved in the work in Brown's Brooklyn studio. Decades later, in May 1886, the Magazine of Western History noted that when workers involved in the "mechanical work" went on strike, Ward convinced Brown they could do the work themselves. "Ward says he passed more days in the bronze horse's belly than Jonah spent minutes in the belly of the whale."

Two weeks before The New York Times editorial, a journalist from the Springfield, Maine, Republican, visited the Ames Manufacturing Company in Chicopee, Maine where the statue was being cast. The newspaper said the work, still in dismembered pieces, "is spoken of in the highest terms of praise."

Brown used the famous bust of Washington executed by Jean-Antoine Houdon in 1785 as his model. He depicted the general on horseback (making this only the second equestrian statue in the United States) and posed him as he might have appeared on Evacuation Day, November 25, 1783.

The morning of July 4, 1856 saw pouring rain in New York City. Nevertheless, a large parade preceded the unveiling ceremonies where newspapers estimated the crown at between 8,000 and 9,000. The weather was not the only glitch in the ceremonies. The coverings became caught and firemen had to erect ladders to disentangle it.

Finally, at about 9:15, the covering fell off and, according to The New York Herald, "the statue was hailed with the most enthusiastic cheers by the crowd...The bands played 'Hail Columbia'--the ladies waved their handkerchiefs--the troops presented arms--the people generally uncovered their heads, and gave vent to their enthusiasm in loud and long continued cheering."

The New York Times reported "The friends of Mr. Brown, the sculptor, pressed around him to shake him by the hand and congratulate him...one man in the throng distinguishing himself above the rest by repeatedly shouting 'Hooray for the architect of the statue."

Brown's larger-than-life statue stood 14 feet, mounted on a granite pedestal of the same height. The body of the horse was cast in a single piece. Washington was dressed in his Continental uniform, his hat resting on his bridle arm and his sword sheathed to his side. His right hand was extended as if he were about to speak. The monument was placed in the triangular traffic island at the southeast corner of the park. According to Helen Henderson in her 1917 A Loiterer in New York, its location was touted as being "the spot where the citizens met the Commander-in-Chief of the army when he reentered the city after the British evacuation, November 25, 1783."

The New York Herald, in reporting on the unveiling, was perhaps the first to heap praises on the work. "Not intending to anticipate the critical opinions which will be showered upon Mr. Brown's work, we may say that it is a great ornament to the finest portion of the Empire city, and that its general effect is highly impressive." Somewhat disappointingly, the young architect who designed the monolithic base got no recognition by any of the critics. Richard Upjohn is remembered today as one of the most important architects of the period.

Suddenly The New York Times had changed its tune. "It is in every way worthy of the highest admiration," it wrote. In a separate article the editor gushed, "We are not sure that any city of the Old world can boast of a more noble work of the kind; we are sure that no city of the New can." It was a compliment that would be echoed again and again.

|

| An early view shows the cast iron lamp posts that surrounded the monument. In the background, left, is the Everett House Hotel. |

In 1878, The Art Journal discussed Brown's works and said, "Nothing can be more harmonious in all respects than his Washington statue in Union Square, New York. The horse is worthy of his rider, but does not divert the mind from the latter." And nearly half a century after the unveiling, in January 1892, Jonathan Gilmer Speed, writing in The Christian Union said "Its dignity and simplicity of treatment impress both the cultivated and the unlearned, and it is not infrequently spoken of as the best equestrian status in this country."

The statue was the scene of ceremonies every subsequent Washington's Birthday and Memorial Day. Union Square was still an upscale residential enclave, and the events sometimes upset the quietude within the homes of residents like Cornelius Roosevelt, who lived directly opposite. On February 21, 1862, for instance, the New York Herald reported on the arrangements for Washington's Birthday. "A national salute will be fired at sunrise at the Equestrian statue of Washington, in Union square."

|

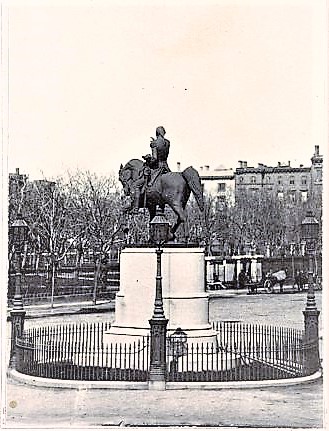

| An 1863 cabinet card, oddly enough, viewed Washington from behind. from the collection of the Library of Congress. |

Two decades after the end of the Civil War the Equestrian Washington statue was the scene of touching, if sometimes mistaken, reverence. On July 3, 1885 an elderly man, Samuel Johnson, fell to his knees before the monument and began praying. The Sun reported "He raised his voice gradually until it became very loud, indeed, and a crowd gathered around him." Overcome with emotion, the gray-haired man rose to his feet and shouted "Lincoln, Lincoln, I owe my freedom to you!"

A policeman pushed through the crowd and tried to persuade Johnson to move along. He continued sobbing and murmuring "Lincoln! Lincoln!" Finally the officer explained that the statue was Washington and that the Lincoln statue was on the opposite side of the park. "The old negro then moved away," said the article. The reporter concluded "He said he was a slave for a man named Bob Jenkins, in West Virginia, and that he had scars on his back from the lashings he had then received."

|

| The massive proportions of the bronze statue were captured in this stereopticon slide. from the collection of the New York Public Library |

The universal esteem earned by Brown's work of art was perhaps best exemplified in 1903 when Adolf Friedmann, an American citizen living in Hungary, presented the city of Budapest with an exact copy. The Evening World reported "The statue was unveiled...in the presence of the members of the American colony of Budapest and of thousands of enthusiastic Hungarians."

In September 1913, Parks Commissioner Charles Bunstein Stover pushed to relocate the statue. The New-York Tribune reported that he "is anxious that the equestrian statue of the Father of His Country now at Union Square, looking north, should look south." He wanted to move it to the middle of the southern edge of the park, where the statue of the Marquis de Lafayette currently stood. Another faction wanted the monument to be moved to Washington Square--a seemingly appropriate site.

It would be 15 years before the statue would be moved to tje site where Stover envisioned it. On April 22, 1928, the Board of Transportation announced intentions to build an ambitious subway concourse below the park. "Extensive changes in Union Square Park will be made necessary by the underground construction," said The New York Times. The entire park had to be excavated and the grade of the park raised to accommodate the underground mezzanines and passageways. "This will involve relocation of the historic statues in the park," said the article.

The monuments and fixtures were taken down, crated, and stored to await the park's reconstruction. When the Equestrian Washington statue was brought back on July 10, 1930, a surprising detail was temporarily visible to New Yorkers. Henry Kirke Brown had included a roster of the wealthy donors' names at the horse's feet. The New York Times reported "As long as the statue remained on its stone pedestal, elevated above the heads of passersby, only spectators who carried ladders as aids to sightseeing were able to notice the list on the flat bronze base of the statue."

Sculptor and chairman of the National Sculpture Society was astonished, saying "This method of memorializing the donors of a statue is unusual," explaining that those names were more commonly encased in a cornerstone. But the Washington statue had no cornerstone.

|

| For a few days in 1930 passersby could view the roster of names as the statue sat on the ground. photographer unknown, from the collection of the Museum of the City of New York |

As the monument was reassembled on its new site, its artistic merit had not dimmed. Parks Commissioner Walter R. Herrick mentioned on July 9, 1930, "artists consider the statue, which is by H. K. Brown, one of the finest equestrian statues in the world."

Union Square suffered a dark period in the late 1960s and 1970s when the city was on the verge of bankruptcy. With no money to maintain it, the park was neglected and became a "needle park," reigned over by drug users and sellers. Monuments throughout the city suffered, including George Washington which lost its bronze sword and bridle strap to vandals.

In 1986, during happier times, the park was renovated. In 1989 the Adopt-A-Monument Program restored the Washington statue, recreating the missing elements.

The monument was a site of Manhattan's collective expression of grief following the World Trade Center attacks. An unofficial shrine developed around its base and a 24-hour community vigil lasted for days.

The monument was restored three more times, beginning that year. In 2004 the bronze was treated and in 2006 Upjohn's granite pedestal was conserved.

The Equestrian Washington--despite an 1855 newspaperman's vehement opposition--is the city's oldest public monument. And more than 160 years after its unveiling it is universally considered a masterwork.

photographs by the author

Union Square suffered a dark period in the late 1960s and 1970s when the city was on the verge of bankruptcy. With no money to maintain it, the park was neglected and became a "needle park," reigned over by drug users and sellers. Monuments throughout the city suffered, including George Washington which lost its bronze sword and bridle strap to vandals.

In 1986, during happier times, the park was renovated. In 1989 the Adopt-A-Monument Program restored the Washington statue, recreating the missing elements.

The monument was a site of Manhattan's collective expression of grief following the World Trade Center attacks. An unofficial shrine developed around its base and a 24-hour community vigil lasted for days.

The monument was restored three more times, beginning that year. In 2004 the bronze was treated and in 2006 Upjohn's granite pedestal was conserved.

The Equestrian Washington--despite an 1855 newspaperman's vehement opposition--is the city's oldest public monument. And more than 160 years after its unveiling it is universally considered a masterwork.

photographs by the author

No comments:

Post a Comment